Samuel JACOB

Year of Birth: 9 August 1907

Place of Birth: Haria, Saparoea

Rank: 2e Luitenant [2nd Lieutenant]

Unit(s): NEFIS Nederland Indië Krachten Intelligentie Dienst [Netherlands East Indies Forces Intelligence Service]

Award: Kruis van Verdienste (KV) [Meritorious Cross]

Died: 7 September 1944

Age: 37 years

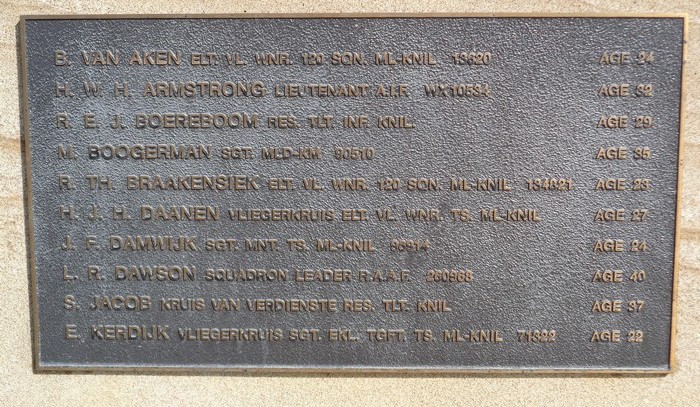

Buried: Cairns War Cemetery – Plot A – Row E – Grave 1 (Coll.)

The Jacob family had originally been an Ambonese family that had been given extensive landholding interests by the Dutch in the colonial backwater of the Aru Islands. Samuel’s father was the local Patti [Chieftain] on the island of Maikoor and his mother was a former schoolteacher from Ambon. Like his mother, Samuel trained as a teacher in the early 1920s and was appointed to teach at a school at Gorontalo on the island of South Sulawesi. There he met another teacher from a similar stratum of Menadonese society, Annie Maas Dumais.

They were married in June 1928 at the local Methodist church and began a family. Through the 1930’s Samuel taught in a variety of locations before he was called back to the Aru Islands by his mother in 1939. His father had died and, while the position was not inherited, the community assumed that he would return and become Patti.

The Dutch also encouraged this plan with the offer of Dutch citizen status. Samuel, however, believed he could make a better contribution to his community as their teacher rather than leader. He made a request to relocate to the Aru Islands and in 1941 he was posted to the island’s administrative centre, Dobo. In 1941 Dobo was a colonial backwater. It was, however, the site of some international intrigue. The Japanese pearling fleet based in Dobo contained a number of Japanese naval intelligence officers who were disguised as pearlers and who were supplying information back to Tokyo on a variety of issues.

The Jacobs were still in Dobo when the Japanese invaded the East Indies in 1942. The Europeans quickly fled, leaving Indonesians such as Samuel Jacob as the representatives of Dutch authority. The departure of the Dutch brought out simmering tensions within this community. The Muslim community was mostly anti-Dutch and was led by a number of Javanese nationalists who had been banished to Aru in the wake of the 1927 communist revolt. The community’s Christians were mostly pro-Dutch. In June the Muslims staged a revolt in anticipation of the arrival of the Japanese. However, the Christians – led by Jacob – successfully put down the rebellion.

In July 1942 the Allies decided to garrison Dobo and sent a mostly Dutch contingent codenamed Plover Force. All Plover Force did was attract Japanese attention to the Aru Islands. A few weeks after the Dutch arrived, the Japanese, led by one of the former Japanese pearlers, invaded and Jacob was arrested. He managed to escape confinement after an Australian reconnaissance plane panicked the Japanese and, minus eldest son Sam, the Jacobs and their 7 other children escaped with the remnants of Plover Force to Darwin. From there in September 1942, they arrived in Melbourne in the corvette HMAS Warrnambool.

The Dutch Indies Government in exile in Australia took care of the Jacob family and housed them in the Metropole Hotel in Melbourne. Samuel, however, was determined to find a house near the water and he and Annie soon found one in the bayside community of Bonbeach. They rented the bottom floor of a house owned by a retired postal clerk called John O’Keefe.

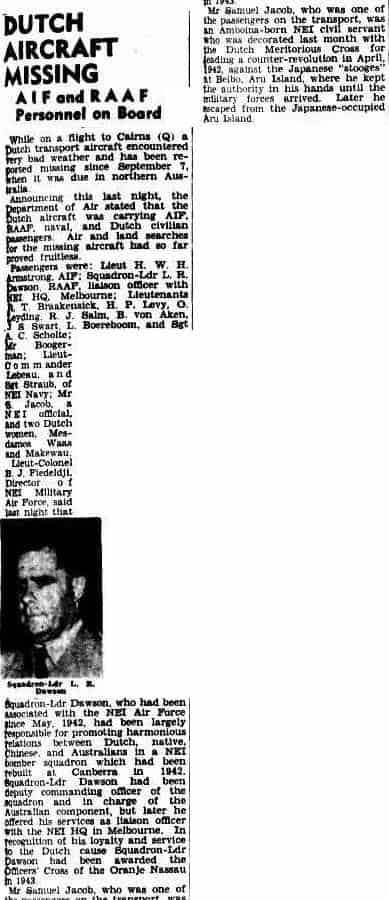

Samuel began working for the Indies Government doing translation work. His skills soon brought him to the attention of the Netherlands Indies Forces Intelligence Service [NEFIS]. He was trained as an operative and went on active duty on at least one occasion far into enemy territory in Indonesia. In September 1944 he was returning to Australia from New Guinea when the plane he was on crashed near Cairns, killing all on board. The Dutch government granted Annie a pension of £28 per month.

In earlier conversation with John O’Keefe, who had kept a small flat on the second floor of the Bonbeach house, Jacob had asked the Australian to look out for his family. With Samuel’s death O’Keefe took up this responsibility and ‘Uncle Jack’, as he was known to the children, played a growing part in the life of the family.

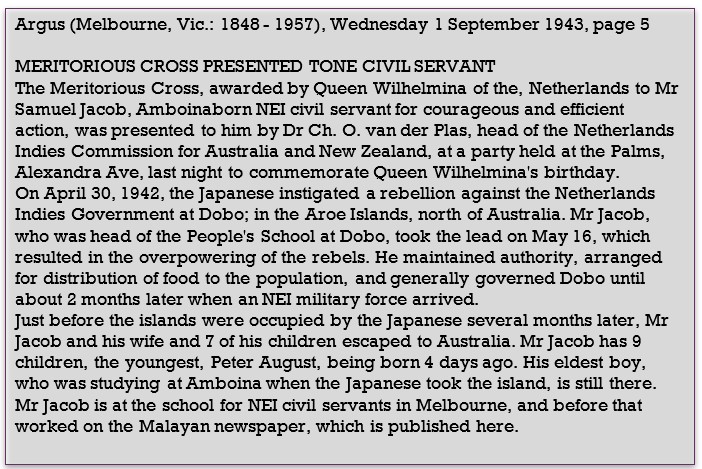

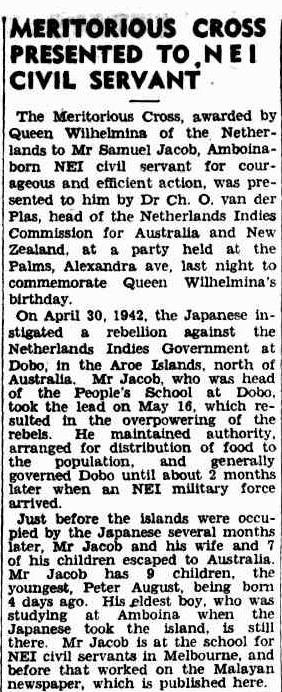

For his actions at Dobo on the Araoe Islands, Samuel was awarded in 1943 by Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands the Kruis van Verdienste (KV) [Meritorious Cross]. .

In early 1942 when the Japanese began occupying the Netherlands East-Indiës (NEI) many Dutch civilians and military personnel were evacuated or escaped to Australia. Some of the Royal Netherlands Navy (RNN) vessels of the fleet also escaped to Australia.

During the war the 1 N.E.I.T.S. [Netherlands East-Indiës Transport Service], provided a regular twice a week route to Merauke from Melbourne via Canberra, Sydney, Brisbane, Townsville and Cairns. It was a four-day round-trip with overnight stays in Brisbane and Merauke.

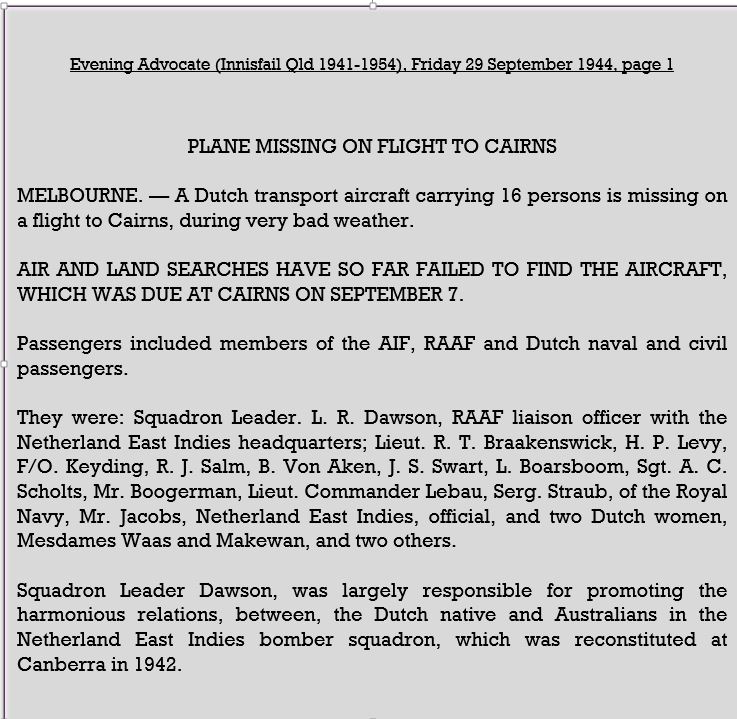

Royal Netherlands East Indiës Air Force C-47 Dakota DT9-41 was on the return leg when it left Merauke air base, Dutch New Guinea Thursday 7 September 1944 bound for Cairns, a flight that usually took about four hours.

On board were 18 Dutch nationals and 2 Australians.

The four crew members of the N.E.I.T.S were Luitenant Hermanus J. H. Daanen, Captain; Sergeant-majoor Willem A. Torn, Co-pilot; Sergeant Jacques F. Damwijk, Engineer; Sergeant Eugene Kerdijk, Wireless Operator.

Members of 120 Squadron NEI-AF who were on their way for some rest and relaxation in Australia: Luitenants Bernard van Aken, Rudolf Braakensiek, Hendrik P. Levy, Otto Leyding, Robert J. Salm and Jan S. Zwart and Sergeant Abraham C. Scholte. Sergeants Martinus J. Straub and Marinus Boogerman of the Netherlands Naval Aviation Service.

Two other pilots who expected to be on the Dakota were reassigned to fly their Kittyhawks to Canberra for maintenance but, their luggage remained on board the Dakota.

Luitenants Robert E. J. Boereboom and Samuel Jacob were Royal Netherlands-East Indies Army officers who were part of the NEFIS [Netherlands-East Indiës Forces Intelligence Service].

Luitenant Commander Joseph R.L. Lebeau of the Royal Netherlands Navy.

Two women civilians, Mevrouw [Mrs.] Waas and Mevrouw [Mrs.] Wakemau who were reported to be with the Red Cross.

The Australian military officers: Squadron Leader Leslie Dawson R.A.A.F. [Royal Australian Air Force] and Lieutenant Hector W. H. Armstrong A.A.S.C. [Australian Army Service Corps].

The crew of the Dakota radioed they would be landing in 10 minutes at Cairns but nothing more was heard from them. They were experiencing bad weather when approaching Cairns in the late afternoon. It was thought the plane crashed into the sea.

An extensive search for the missing plane was undertaken by the Air Force over the sea and land, and were supported by the army, police, and scores of civilians in remote areas. No trace of the plane could be found, and the search was called off after three weeks by the Dutch authorities.

Wreckage of the plane was discovered 45 years later in January 1989 by seven members of the Australian New Zealand Scientific Exploration Society (ANZSES) when they were collecting plant specimens on the mountain peaks north-west of Mossman, North Queensland.

They contacted Air Force officials in Canberra about their find. The registration markings still visible on the tail confirmed it was the missing plane.

News of the discovery was sent to The Hague in the Netherlands and so began the difficult task of tracking down and notifying the next of kin.

Permission was given on Tuesday 24 January 1989 for a recovery mission to retrieve the remains of the passengers and the many personal items from amongst the crash debris. Access to the site was only accessible by helicopter. The operation was conducted by No. 27 Squadron with the helicopter support from No. 35 Squadron, Townsville. The mission concluded on Saturday 11 February 1989.

On Saturday 29 July 1989 the remains of the 20 crash victims were laid to rest together in a large single grave in the Cairns War Cemetery with full Military Honors.

The armed honor guard at the monument consisted of special units of the Australian land, air and naval forces.

Relatives, especially from America, Netherlands and Australia that had traveled to Cairns, were highly impressed with the ceremony.

In 1993 all were registered in the Queensland Birth Death and Marriage register with the death recorded as 7 September 1944.

With the end of the war the Australian Government moved to repatriate all Asian ‘evacuees’. Because of the unsettled situation in Indonesia and the educational needs of the children, the Jacob family was allowed to stay for some time but by 1947 the Australian Government wanted them gone.

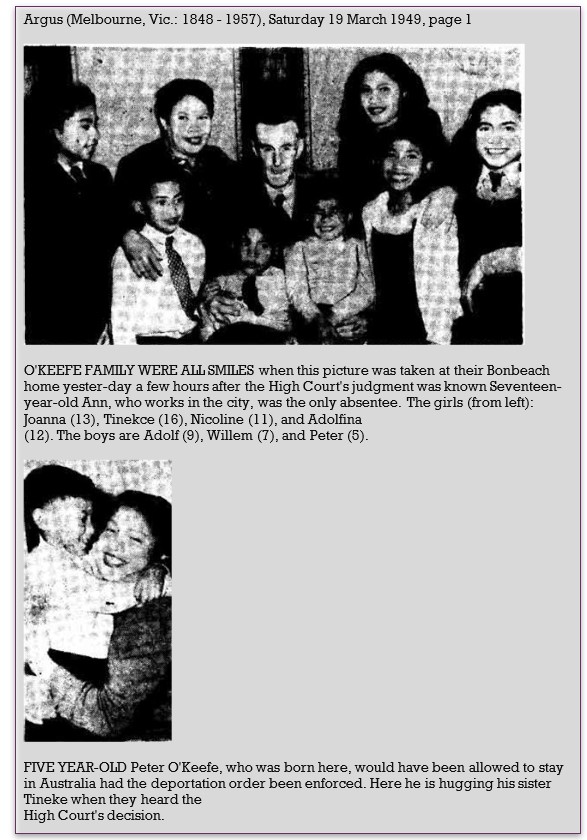

While Annie had lost her Dutch citizenship on marriage to John O’Keefe, the Australian Government refused to recognise that the marriage gave her any residency rights in Australia. The government did, however, issue the family with a Certificate of Exemption from the Immigration Restriction Act 1901–1948 to allow the children to further their education and wait for the situation in Indonesia to become more settled. The issue dragged on until early 1949 when finally, Arthur Calwell moved to deport the family. This led to a High Court case and the first successful legal challenge to the White Australia Policy.

The eldest son Sam was never allowed to enter Australia while his sisters Ann, Tineke, Joanna, Adolfina, and brothers Adolf and Willem were allowed to also remain in Australia. The youngest Peter was born in Australia.

John and Annie O’Keefe had a daughter, Geraldine.

The O’Keefe’s legal team had a two-pronged attack. First, they argued that Mrs O’Keefe could not be deported because she was not an ‘immigrant’. She and her children had been ‘assimilated’ into the Australian community. Secondly, the government was deporting Mrs O’Keefe by revoking the Certificate of Exemption she had been issued in 1947. Taking the argument over Mrs O’Keefe’s immigrant status further, her barristers argued she was not eligible to receive such a certificate in 1947 because she had never been classified as a prohibited immigrant on grounds of personal deficiency or a failure to pass the Dictation Test. Because of the nature in which the Jacobs had entered Australia they had never sat the Dictation Test. She entered the Commonwealth openly while under the control of naval authorities.

Annie (Jacob) O’Keefe died in 1974.

Online Resources

Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Awards to the Dutch for the Second World War

AFC and Royal Australian Air Force Association Queensland Division Cairns Branch

Military Aircraft Crashes in Australia during WW2-Oz At War

National Library of Australia: Trove Digitised Newspapers

Queensland Registrar of Births Deaths & Marriages

Victorian Births Deaths and Marriages

If you have a photograph or further information about this soldier you would like to share and add to his biography, please contact the Society at projects@cdfhs.org or leave a comment below. Thank you!